Unique Japanese words

Translating between different languages isn’t the easiest task, especially when there are culturally specific concepts or words that don’t have equivalents in other languages. Here are some unique Japanese words that simply can’t be translated to encapsulate the profound meaning in its original language.

For more language guides, check these out:

- Japanese buzzwords in 2020

- Loanwords that mean different things in their original language

- Tips to speak like a Japanese native

1. Mottainai (勿体ない)

Image credit: @quizmanjpn

Mottainai (勿体ない) is a word that is unique to the Japanese. It can be translated to mean “what a waste” or “such a pity”, but it doesn’t nearly convey the feeling of guilt or apology in its original language. The word is used to express a sense of regret when something useful is unnecessarily discarded instead of utilising it to the fullest extent.

The usage is not exclusive to objects. When used on people, it is implied that one is not good enough for their significant other, or doesn’t deserve an expensive present when gifted one.

2. Mono no aware (物の哀れ)

Image credit: Evgeny Lazarenko

An aesthetic and literary philosophy that dates back to as early as the 6th century, mono no aware (物の哀れ) literally translates to “the sorrow of things”. Simply put, it is the sobering awareness that nothing in life lasts.

But, as melancholic as that is, it’s exactly the impermanence of things – such as nature and human existence – that allows one to appreciate the beauty of fleeting moments even more. The term is often associated with cherry blossoms, as the brief beauty of the pink blooms is all the more cherished when spring comes.

3. Wabi sabi (侘び寂び)

Image credit: pepe nero

Advocating the embracement of imperfection and appreciation of ageing, wabi sabi (侘び寂び) is an aesthetic that stems from ancient Buddhist teachings. The word amalgamates the nouns “wabi” and “sabi”, where the former refers to an appreciation for modesty and simplicity, while the latter refers to the beauty that comes with wear and tear.

If you find the concept elusive, look no further than tea ceremonies, pottery, and even Zen gardens to understand the meaning of wabi sabi. Many of these traditional artistic forms convey the muted, rustic beauty that encapsulates the idea of wabi sabi.

4. Omotenashi (お持て成し)

Image credit: @umegaka

The term “omotenashi” (お持て成し) was probably unheard of outside Japan until Christel Takigawa, a French-Japanese newscaster, made international headlines with her captivating presentation for the International Olympic Committee.

When broken down, “omote” means the image that you put up in public, and “nashi” translates to “without”. Essentially, omotenashi refers to a sincere form of hospitality that is characterised by the commitment to providing superb customer service and being attentive to the needs of your guests.

5. Yūgen (幽玄)

Image credit: @sunset.beach_

Yūgen (幽玄) refers to a form of traditional Japanese aesthetic. Often regarded as untranslatable or difficult to define at best, the meaning of yūgen changes over time and depends on the context in which it’s used. Most commonly, it is described as an enigmatic form of expression, typically used in classical Japanese poetry (和歌; waka), to express the profound beauty of what is not said or seen.

6. Komorebi (木漏れ日)

Image credit: @hisa_azm

There’s arguably nothing better than the feeling of warm, gentle sun rays hitting your skin on a chilly day. While there’s no word in English to describe the sensation, the Japanese expression “komorebi” (木漏れ日) perfectly encapsulates and describes the gentle rays of sunlight that leak through trees.

7. Osusowake (お裾分け)

Image credit: @teruyo118

From celebratory gifts during special occasions to obligatory souvenirs, gift-giving is a custom that permeates every aspect of Japanese culture. But if you happen to receive something you don’t or can’t use, it’s common to share with others what you’ve received through what is known as osusowake (お裾分け).

That’s not to say that you’re being disrespectful to the giver – the sharing is done with a sense of gratitude and an acknowledgement of the other party’s thoughtfulness.

8. Ukiyoe (浮世絵)

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Though better known as a type of Japanese woodblock print, ukiyoe (浮世絵) translates literally to “pictures of the floating world”, which is rather poetic. Depicting the everyday life of early Japan, this genre of prints came into vogue during the Edo Period.

In Japanese, ukiyo also refers to the pleasure and entertainment quarters of Edo, which is what the modern–day Tokyo was known as. Thus, many of the subjects include well-known courtesans, kabuki actors, and sumō wrestlers. Aside from portraits of humans, natural landscapes were also popular subjects for ukiyoe artists.

9. Tsundoku (積読)

Image credit: Florencia Viadana

If you have a habit of buying new books with the intention of reading them but never get around to doing so, here’s a term in Japanese that describes you. Tsundoku (積読) is the act of hoarding books, so much so that you have them piled up in the corner of your room. It combines the verbs “tsumu” (積む; to accumulate) and “yomu” (読む; to read).

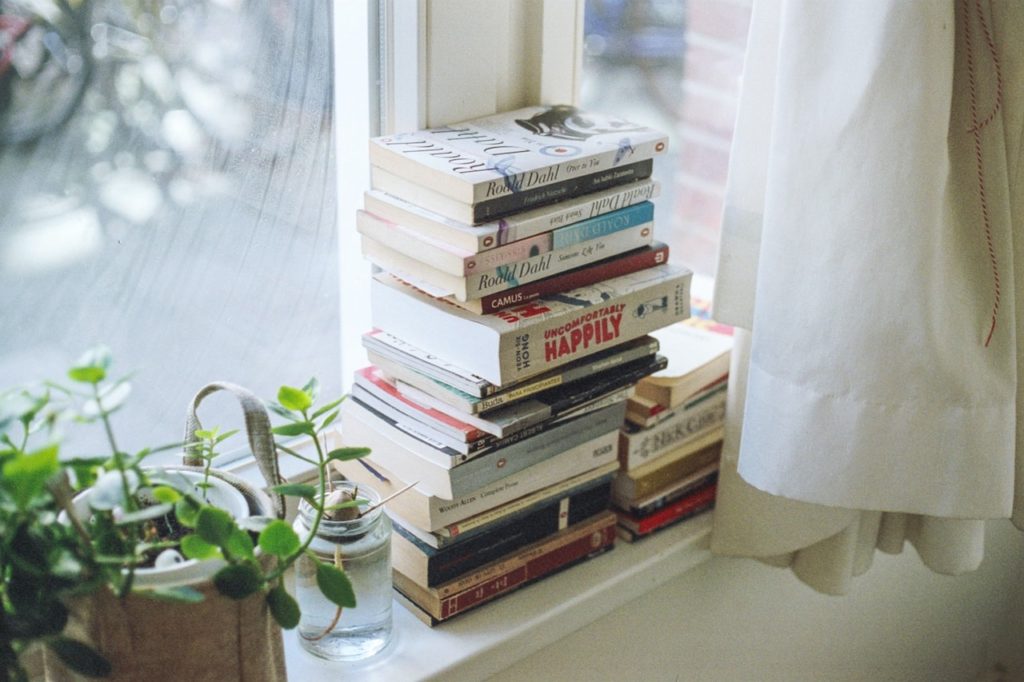

10. Kogarashi (木枯らし)

Image credit: @choro.rin

Winter is often associated with a white, powdery blanket of snow, but along with the chilly season comes strong gusts of cold wind. Kogarashi (木枯らし) refers to the harsh icy wind that is so cold that it dries up foliage. The crisp winter air usually signals the end of autumn and the start of a cold season.

11. Shinrinyoku (森林浴)

Image credit: @oignonsho

It’s no secret that being surrounded by nature helps calm minds and relaxes the body. In Japan, shinrinyoku (森林浴), also known as “forest bathing”, is a form of therapy that involves spending time in a tranquil forest.

This method of therapy has been scientifically backed and proven to aid in spiritual healing, and it is said to be particularly beneficial for reducing stress and anxiety. In the 1980s, the Japanese government advocated the practice by encouraging citizens to regularly go on walks in the forest.

12. Arigata meiwaku (ありがた迷惑)

Image credit: @boku_pocha

Perhaps the pinnacle of Japanese politeness, arigata meiwaku (ありがた迷惑) can be best translated as a sarcastic “thank you for the inconvenience caused”. Fusing together “arigatai” (gratitude) and “meiwaku” (inconvenience), the phrase is a bit of an oxymoron.

But it makes total sense as it describes a predicament where someone insists on doing you a favour you don’t need and ends up causing you trouble. Instead of showing your annoyance, you have to express gratefulness nonetheless due to social conventions.

Unique Japanese words that are untranslatable

Some words get lost in translation, while others are so abstract that they require lengthy explanations before we can make sense of them. What are some of your favourite unique Japanese words that are impossible to translate smoothly into other languages?

Check out these articles if you’re interested in Japanese culture and language:

- Japanese slang to know

- Kyoto cafes in heritage buildings

- Everyday mysteries in Japan

- Summer activities in Japan

- Essential Japanese phrases

Cover image adapted from (clockwise from left): @boku_pocha, pepe nero and Florencia Viadana