Comprehensive guide to Japan shrines

Shinto shrines can be found everywhere in Japan. But for the uninitiated, it may be daunting to approach a sacred site, let alone enter it. To help you along, we’ve compiled a comprehensive guide to understanding shrines in Japan. Read on for the ultimate guide to the different types of shrines, common features, and the dos and don’ts when visiting.

Table of Contents

- Comprehensive guide to Japan shrines

- – Shrine title –

- 1. Jingū

- 2. Gū

- 3. Taisha

- 4. Jinja

- 5. Hokora

- – Types of shrines –

- 1. Inari shrine

- 2. Hachiman shrines

- 3. Tenmangu

- 4. Shinmei shrines

- 5. Asama shrines

- 6. Kumano shrines

- 7. Local shrines

- – Common objects –

- 1. Torii

- 2. Sandō

- 3. Chōzuya

- 4. Kagura-den

- 5. Saisen-bako

- 6. Omamori

- 7. Omikuji

- 8. Shimenawa

- 9. Goshuin

- 10. Ema

- 11. Tōrō

- 12. Komainu

- 13. Chinowa

- – Etiquette to follow –

- 1. Don’t walk in the middle of the sandō

- 2. Purify your hands and mouth at chōzuya

- 3. Use 5 yen for offering

- 4. How to pray

- 5. Bow once more when you leave

- All you need to know about Japan shrines

– Shrine title –

1. Jingū

Meiji Jingū in Tokyo

Image adapted from: @angharaya

Jingū (神宮) is a status given to shrines that enshrine emperors or members of the imperial family. This type of shrine has a deep connection to the imperial family of Japan. For example, Meiji Jingū is dedicated to Emperor Meiji, the 122nd Emperor of Japan, and his wife Empress Shōken.

2. Gū

Tōshōgū in Nikko

Image credit: @komadiary

After jingū comes gū (宮), the 2nd most prestigious status that can be accorded to a shrine. Gū is generally dedicated to imperial princes, people who are closely related to the emperor, and important historical figures. Tōshōgū, a lavish shrine located in Nikko, enshrines Tokugawa Ieyasu, who’s 1 of the 3 Great Unifiers of Japan.

3. Taisha

Izumo Taisha in Izumo

Izumo Taisha in Izumo

Image credit: @no.__.on_0223

Literally translated to “grand shrine”, the title “Taisha” (大社) is given to shrines that are rooted in local beliefs or simply large in size. Originally, the term was exclusive to Izumo Taisha, a shrine in the city of Izumo. It is widely considered to be one of the oldest shrines in Japan. But the title became increasingly common in the post-war period and was adopted by many shrines.

4. Jinja

Image credit: DEAR

Jinja (神社) is a generic term for shrines. Any place that comprises a honden (main hall; 本殿), which enshrines the spirit of a deity, can be called a jinja. Used to distinguish it from temples, this title is the most common one that can be given to shrines.

5. Hokora

A hokora along the Isumi Line in Chiba

A hokora along the Isumi Line in Chiba

Image credit: @mugiwara.pota

Hokora (祠) refers to small shrines that are often found along roadsides or in obscure places, such as deep in a forest. Unlike other types of shrines, there are often no torii gates at a hokora. Even if there is one, they tend to be very small. These miniature shrines are typically dedicated to kami who don’t belong to the larger shrines.

– Types of shrines –

1. Inari shrine

Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto

Image credit: @nicci.travels

Inari shrines (稲荷神社) are dedicated to Inari Ōkami, a god associated with rice, foxes, bountiful harvest, and business prosperity. They have the largest number of branch shrines in Japan, with approximately 32,000 Inari shrines scattered across the country, and the famed Fushimi Inari Taisha is the head shrine.

Since ancient times, foxes have been regarded as the messengers of the Inari god. Hence, you’ll likely spot foxes instead of komainu (custodian lion-dogs) statues guarding Inari shrines.

2. Hachiman shrines

Usa Jingū in Oita

Image credit: @trip2local

The next most common type of shrine is Hachiman (八幡神社), which enshrines the kami Hachiman. Hachiman is the deification of Emperor Ōjin, the 15th emperor of Japan. He is regarded as the god of agriculture, sea, and war. There’s a vast network of Hachiman shrines all over the country, but the head shrine, Usa Jingū, is located in Usa City of Oita Prefecture.

3. Tenmangu

Dazaifu Tenmangu in Fukuoka

Dazaifu Tenmangu in Fukuoka

Image credit: @dazaifutenmangu.official

Tenmangu (天満宮) worships Sugawara no Michizane, a renowned scholar and poet from the Heian Period. History has it that in order to appease the wrath of the scholar, who died after he was unjustly exiled, Kitano Tenmangu was built in Kyoto and dedicated to him. He was later deified as the kami Tenjin, an abbreviation of “Tenmandaiji Zaitenjin”.

As an exemplary scholar of his time, Sugawara no Michizane is worshipped as the god of learning today. Students usually pray at Tenmangu for academic success, and he’s considered a household name.

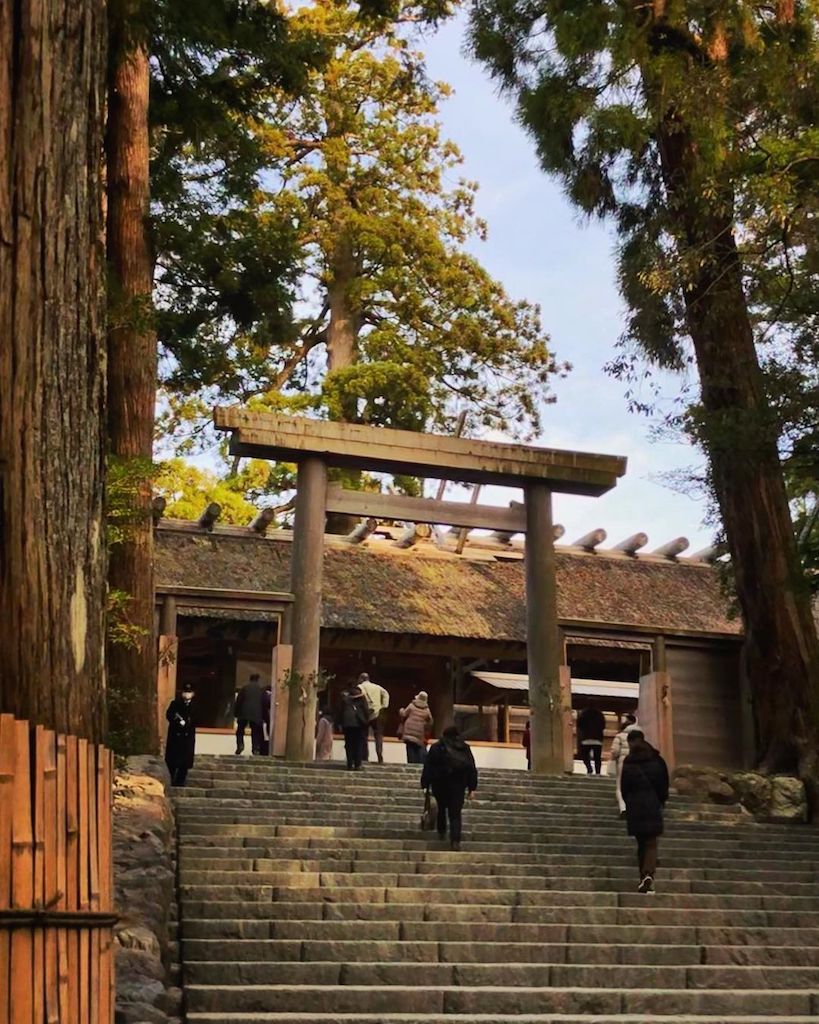

4. Shinmei shrines

Ise Jingū

Image credit: @riku_riko_father

Shinmei (神明神社) refers to shrines that worship the sun goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami, one of the most important deities in Shinto belief. Devotees believe that she is an ancestral god of the imperial family.

In ancient times, the supreme deity was only enshrined in Ise Jingū and worshipped by members of the imperial court. However, as the influence of the imperial family declined, branch shrines devoted to Amaterasu popped up nationwide over the years.

5. Asama shrines

Kawaguchi Asama Shrine

Kawaguchi Asama Shrine

Image credit: @yamadiary

Asama shrines (浅間神社) are shrines specifically built to revere the god of volcanoes, Princess Konohanasakuya. As such, you’ll spot most Asama shrines situated in the vicinity of Mount Fuji.

Asama shrines were built to placate the volcanic god and keep the region safe. Though the iconic mountain last erupted in 1707, Mount Fuji is still considered an active volcano as volcanic activity has been detected since the end of the Nara Period.

6. Kumano shrines

Kumano Nachi Taisha in Wakayama

Image credit: @oskerwyld

One of Japan’s most sacred regions, the 3 Kumano mountains are worshipped and enshrined as deities in Kumano shrines (熊野神社). There are over 3000 Kumano shrines in Japan, but the 3 head shrines situated in Wakayama Prefecture are collectively referred to as the Kumano Sanzan. Due to the popularity of the Kumano pilgrimage route in the ancient times, the faith, alongside branches of Kumano shrines, spread nationwide.

7. Local shrines

Momotaro Jinja in Inuyama

Momotaro Jinja in Inuyama

Image credit: @anmitsu703

While most shrines are associated with established networks, smaller shrines devoted to local god or folklore can still be found in every corner of Japan. Though local shrines may not be as well-known as their bigger counterparts, they can be quite quirky. For example, Inuyama city’s Momotarō Jinja is connected to the fabled folklore Momotarō, which follows the adventures of a demon-slaying peach boy.

– Common objects –

1. Torii

Image credit: @ryokohayashibe

One of the key features that sets shrines apart from temples is torii (鳥居), traditional gates that are commonly erected at the entrance of, or within shrines. The gate serves to demarcate the boundary between the ordinary world and sacred space.

Generally, torii can be categorised into 2 types – myōjin (明神) and shinmei (神明). You can recognise the former by its distinctive curvatures and varied shapes, while the latter comprises strictly straight pillars.

2. Sandō

Image credit: @ree.s.mdragon

Upon entering the torii, you’ll find yourself on a walkway that leads you to the shrine’s main hall. Known as “sandō” (参道) in Japanese, the path is usually lined with lanterns or large trees that are part of the surrounding sacred forest (chinju no mori; 鎮守の森).

3. Chōzuya

Image credit: @tamaju_travel

Before making their way to the main hall, visitors must first symbolically purify themselves at the chōzuya (手水舎). Usually located near the entrance of shrines, these pavilions have a huge basin filled with clean water, with ladles (柄杓; hishaku) provided. Visitors have to wash their hands and rinse their mouths here.

4. Kagura-den

Image credit: @ichiro.image

The ancient Shinto ritual kagura, a traditional and sacred dance dedicated to the kami, is performed at the kagura-den (神楽殿). Depending on the shrine, the size and style of a kagura-den varies. When it’s used as a worship hall (拝殿; haiden), the kagura-den can be bigger than the main hall. It can also be a plain structure or one that’s lavishly decorated.

5. Saisen-bako

Image credit: @momo.sak

Image credit: @momo.sak

A request to the kami is often accompanied by saisen, which are offerings or donations. Before making their wish, visitors would toss coins into a saisen-bako (賽銭箱), a wooden box used to collect donations.

6. Omamori

Image credit: @hinajapon

Image credit: @hinajapon

Those who need a little extra luck or protection can purchase an omamori (お守り; amulet). These colourful amulets are essentially portable good luck charms designed to bless you in specific aspects of your life, from academic success to traffic safety. In Japan, it’s also common to present them as gifts when you want to convey your well wishes.

7. Omikuji

Image adapted from: @k.nakakou_

Image adapted from: @k.nakakou_

Omikuji (御神籤) refers to paper fortune slips that are sold for ¥100- ¥300 (~USD0.96-USD2.89) at shrines. The slips predict your fortune in all aspects of your life, so they are particularly popular during the New Year.

Depending on what you draw, you can be blessed with anything from excellent luck (大吉; daikichi) to terrible luck (大凶; daikyō). If you get anything less than satisfactory, remember to tie the paper slips on pine trees or racks available at the shrine to leave the bad luck behind.

8. Shimenawa

Shimenawa at Izumo Taisha

Shimenawa at Izumo Taisha

Image credit: @happy_trip_68

Typically made with rice straw, shimenawa (しめ縄) refers to sacred twisted ropes used to demarcate consecrated spaces and ward off evil spirits.

Size-wise, there’s a wide range in diameter and length, but the biggest and most well-known shimenawa is the one at Izumo Taisha, and it measures over 8m in width. You’d be able to find shimenawa on torii gates and even around ancient trees.

9. Goshuin

Image credit: @itsukusima_m

Image credit: @itsukusima_m

A goshuin (御朱印) is a type of commemorative stamp that’s unique to shrines and temples. For a modest fee (¥300- ¥500, ~USD2.89-USD4.82), visitors can get a seal stamped on their goshuinchō (御朱印帳) – a book specifically used to collect said stamps – complete with gorgeous handwritten calligraphy.

10. Ema

Image credit: @3491hipu

Image credit: @3491hipu

If you have a wish, pen them down on an ema (絵馬), a small wooden tablet adorned with a drawing of a horse. In the past, horses were dedicated to deities in exchange for wishes. As it’s not exactly possible to gift a horse every time you need to make a wish in modern times, the olden practice has been replaced with more feasible horse drawings.

After the plaque has been inscribed with wishes, it is hung and displayed at the shrine. Most ema are pentagonal or rectangular, but you can also find ones in unconventional shapes these days.

11. Tōrō

Image credit: @usako0225

Image credit: @usako0225

Lined in neat rows along the sandō, tōrō (灯籠) is a type of traditional Japanese lantern. Though it used to be exclusive to Buddhist temples, its use became widespread during the Heian period and it’s now a common feature of Shinto shrines. From hanging lanterns to those made from stone, the varieties of tōrō that can be found at shrines are aplenty.

12. Komainu

Image adapted from: @tanpopofilm

In Japanese mythology, komainu (狛犬), a hybrid lion-dog creature, serve as messengers for deities. As the guardian beast also protects the shrine by warding off evil spirits, it is customary to place a pair of custodian beasts on both sides of the entrance or within the shrine complex.

13. Chinowa

Image adapted from: @no111bloom

At the height of summer every year, shrines around Japan will put up chinowa (茅の輪), a large ring made from cogon grass. The set-up is part of an ancient purification ritual called the Nagoshi no Harae (夏越の祓). Visitors have to pass through the chinowa thrice in order to purify their mind and body, as well as to ward off misfortune.

– Etiquette to follow –

1. Don’t walk in the middle of the sandō

Image adapted from: @too.too.084

When walking up to the main shrine, many tourists make the rookie mistake of walking right smack in the middle of the path. While it’s not the most terrible faux pas, it may raise a few eyebrows.

The centre of the sandō, also known as the seichū (正中), is said to be the path that the kami takes. So when you’re walking on the main approach, be sure to scooch over to the side.

2. Purify your hands and mouth at chōzuya

Image credit: Bryan Choo

Image credit: Bryan Choo

The purification process may seem convoluted for first-time visitors, but just remember this hard-and-fast rule – you start and end with the ladle in your right hand.

First, pick up the ladle with your right hand, scoop a ladleful of water, and pour some over your left hand. Pass the ladle to your left hand and repeat the same process for your right hand.

Then, hold the ladle with your right hand again, scoop more water from the basin, and transfer the water to your cupped left hand. Use the water to rinse your mouth. Finally, lift the ladle perpendicular to the ground so that excess water flows down the handle.

Make sure to do your cleansing over the drain as you wouldn’t want used water to contaminate the entire basin.

3. Use 5 yen for offering

Image credit: @shiromokonano

Image credit: @shiromokonano

Once you get to the worship hall, you should first ring the bell. After that, it’s common practice to make a small offering before you pray. There are no restrictions to how much you should give, but coins are popular choices.

In particular, 5 yen coins are typically given as its pronunciation in Japanese, “go-en”, is a homophone for “御縁”, which means “ties”. Offering 5 yen coins thus symbolises having a good relationship with the deity of the shrine.

4. How to pray

Image credit: Kentaro Toma

Image credit: Kentaro Toma

After you’ve made your offering, bow twice. Make sure that you straighten your back and bow deeply. Bring your hands to your chest level and clap twice, then put your hands together and pray with all your heart. Once you’re done praying, make 1 more bow.

5. Bow once more when you leave

Image adapted from: @yizhao.jiateng

Image adapted from: @yizhao.jiateng

When leaving the shrine, it’s necessary to bow once more to express your gratitude to the kami. Exit the shrine via the torii or entrance, turn your body to face the shrine, and bow 1 last time.

All you need to know about Japan shrines

Now that you’ve taken what is essentially a crash course in the basics of Japan shrines, you’ll be able to blend in seamlessly with the locals and avoid committing any faux pas when visiting one. Use your newly acquired knowledge and go forth shrine-hopping in Japan!

For more cultural pieces, check these out:

- Japanese books about contemporary Japan

- Buzzwords of 2020

- Transportation in Japan

- Centuries-old sustainable habits in Japan

- Everyday mysteries in Japan

Cover image adapted from (clockwise from left): @oskerwyld, @itsukusima_m and Bryan Choo