Japan then and now

With history dating back thousands of years, the Land of the Rising Sun has seen remarkable transformations through the ages. From the abolishment of the feudal system less than 2 centuries ago to a post-war economic miracle, places and monuments bear witness to Japan’s development.

While some places remain in pristine condition, others have given way to modernisation. Here are 20 photos of Japan then and now to show how the country has really – or not – changed.

1. Mount Fuji

Photograph of Mount Fuji (1935) by Okada Kōyō (left) and present (right)

Photograph of Mount Fuji (1935) by Okada Kōyō (left) and present (right)

Image adapted from: Yamanashi Tourism Organization and @mmeegguuuu

A well-known cultural icon both domestically and internationally, the snow-capped Mount Fuji is located on Honshu Island and stands on the border between Shizuoka and Yamanashi Prefectures. At 3,776 metres, it’s Japan’s tallest mountain.

Photograph of Mount Fuji (1930) taken from a small village near Oshino Hakkai, by Okada Kōyō

Image credit: Yamanashi Tourism Organisation

Affectionately called Fuji-san (富士山) by the Japanese, the san can be taken as a pun as it sounds like an honorific suffix used to address people.

Oshino Hakkai today, a popular tourist destination

Image credit: @_take_taro_

While the mountain itself has not changed much, its surroundings are no longer recognisable – what used to be rural have since given way to high-speed railway lines and popular tourist attractions.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, a woodblock print by Hokusai (1830s)

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, a woodblock print by Hokusai (1830s)

Image credit: Wikipedia

The ubiquitous icon has served as a muse for Japanese artists, writers, poets, and photographers throughout history. Most notably, The Great Wave off Kanagawa by woodblock print artist Hokusai, from his series Thirty-Six Views Of Mount Fuji, was inspired by this mountain.

Address: Chūbu region, Honshu, Japan

2. Ameyayokocho – Tokyo

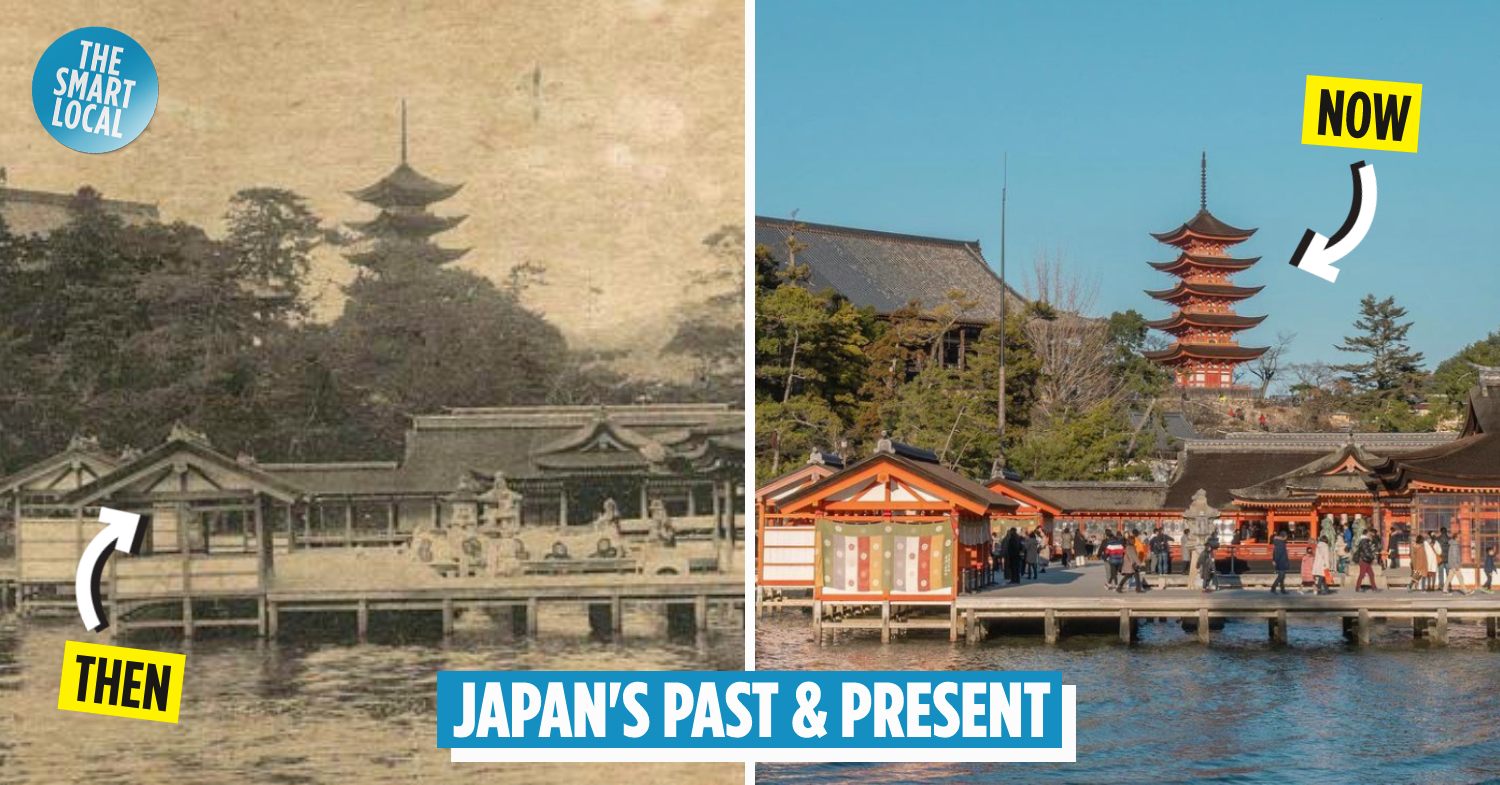

Ameyayokocho in the 1950s (left) and 2015 (right)

Ameyayokocho in the 1950s (left) and 2015 (right)

Image adapted from Gonzo Shouts and @makimaki701

Ameyayokocho (アメヤ横丁) used to be a black market where people gathered in search of food and jobs during the post-war period.

Now an open-air market, the street offers a huge range of goods for a reasonable price, such as makeup, apparel, medicine, and even dried goods.

Post-war Ameyayokocho

Image credit: Gonzo Shouts

There are various theories for how the name came to be. Back then, many street vendors sold candied sweet potato at a time when sweets were considered a precious commodity.

Over time, the market came to be known as ameya (飴屋) yokocho (横丁). “Ameya” refers to “candy shops” and “yokocho” means “alley” – together, it means “an alley that is filled with candy shops”.

Ameyayokocho in 1978

Image credit: tsunechan.web

Another theory is that due to the Korean War, many stores started selling surplus American military goods procured from the troops – so “ame” (アメ) can also be short for America (アメリカ).

Address: 4 Chome-9-14 Ueno, Taito City, Tokyo 110-0005, Japan

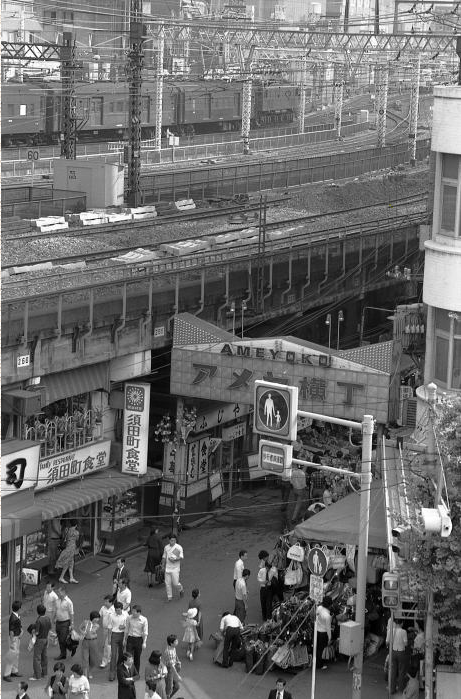

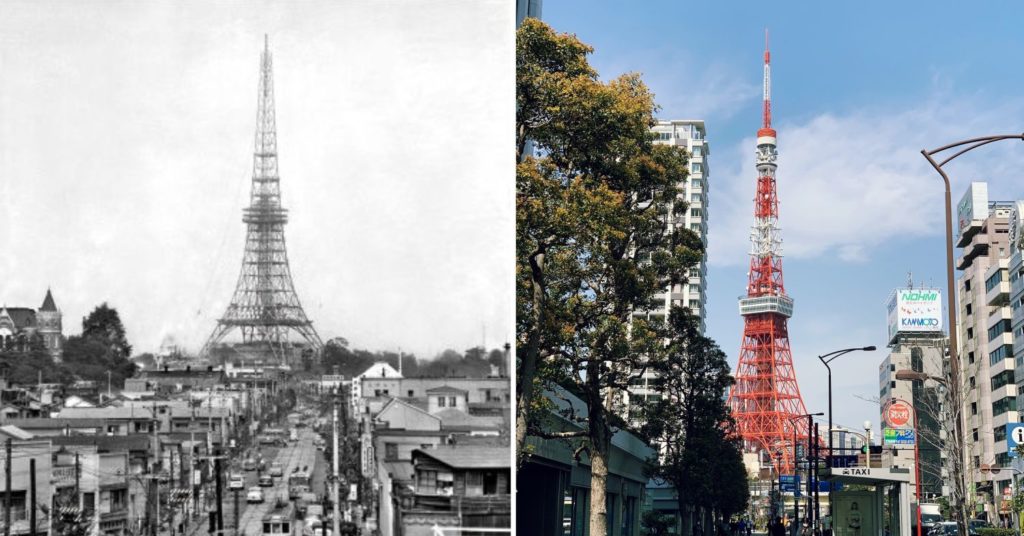

3. Tokyo Tower – Tokyo

Tokyo Tower in 1958 (left)

Tokyo Tower in 1958 (left)

Image adapted from Livedoor and @maiko628923

Completed in 1958 amidst rapid economic growth, the Tokyo Tower was hailed as a symbol of the nation’s renewal and hope for the future.

Contrary to popular belief, the red and white two-tone colour is actually “international orange” and white – colours specified by international aviation law at the time for buildings over a certain height.

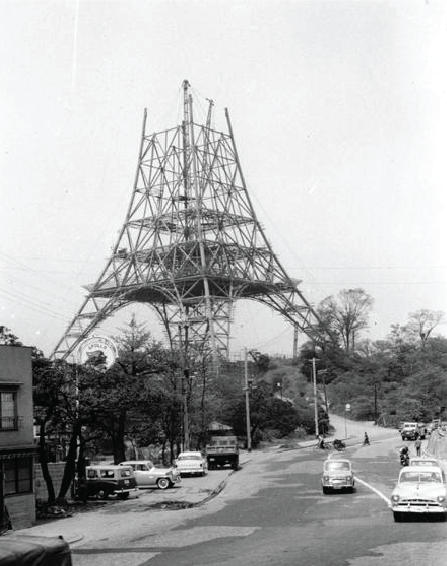

Tokyo Tower in the middle of construction

Image credit: Bird Yard

Initially, the functions were more pragmatic than decorative – Japan needed one tall transmission tower capable of serving the increasing number of broadcasting stations that sprung up across regions in the 1950s.

Image credit: @sakaki0325

The tower was thus instrumental in helping to spread mass media in post-war Japan, especially television. Unfortunately, in 2008, it lost its place as the nation’s broadcasting tower to a taller, newer Tokyo Skytree.

Nevertheless, it remains an icon of Tokyo and is immensely popular among tourists.

Address: 4 Chome-2-8 Shibakoen, Minato City, Tokyo 105-0011, Japan

4. Harajuku Station – Tokyo

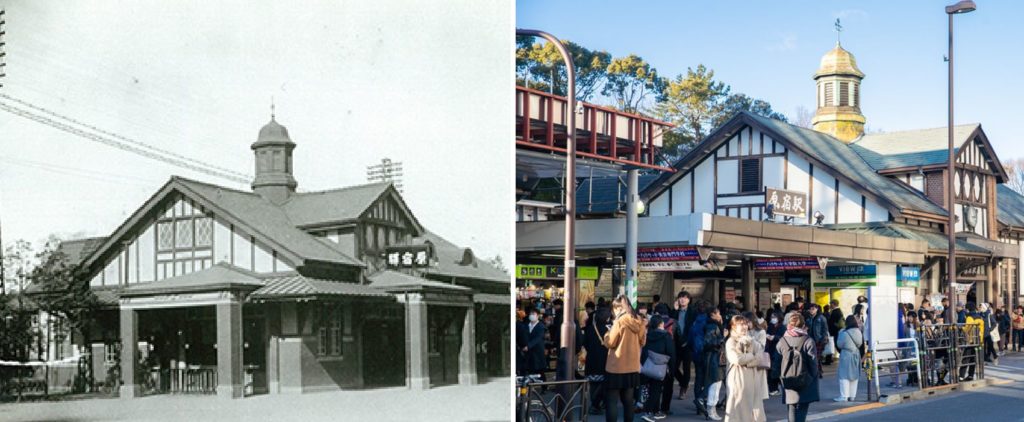

Harajuku Station in 1906 (left) and before it was demolished in 2020 (right)

Harajuku Station in 1906 (left) and before it was demolished in 2020 (right)

Image adapted from: Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Realty Co and Dick Thomas Johnson

The unofficial gateway to the hotspot of youth culture and trendy fashion in Tokyo, Harajuku Station is located near popular landmarks such as Takeshita-dori and Meiji Shrine.

When it was built in 1906, the station received few passengers daily until Meiji Shrine was completed in 1920. Foot traffic drastically increased as shrine-goers would commute to the nearby Harajuku Station. The station then underwent a facelift in 1924 with an English style wooden exterior.

New Harajuku Station in 2020

Image credit: Dick Thomas Johnson

Despite its charming exterior, the building was deemed unsafe as it no longer complies with Tokyo’s fire safety codes. It eventually gave way to a modern station with a sleek glass exterior in March 2020, located just south of the old building.

Address: 1 Chome Jingumae, Shibuya City, Tokyo 150-0001, Japan

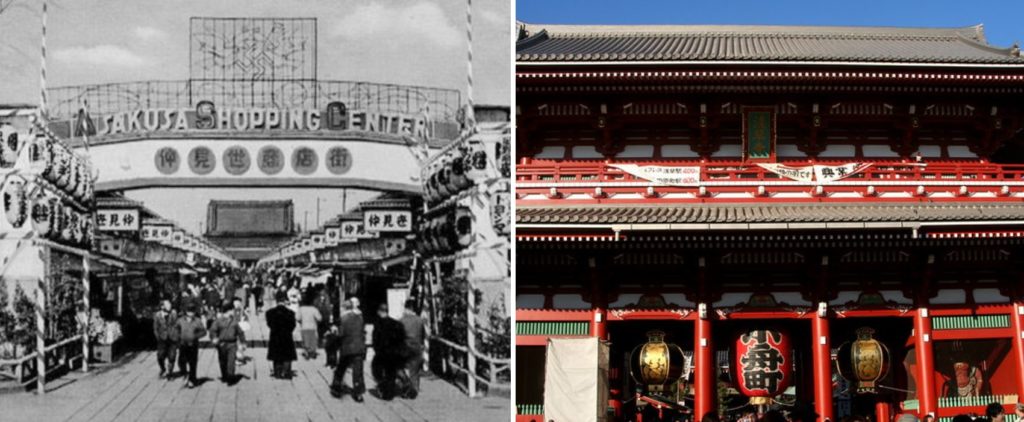

5. Kaminarimon (Thunder Gate) – Tokyo

Makeshift Kaminarimon in 1866 (left) and now (right)

Makeshift Kaminarimon in 1866 (left) and now (right)

Image adapted from: Livedoor and machu.

An iconic landmark of Asakusa, the imposing Kaminarimon (雷門), or “Thunder Gate”, is the main entrance that leads to Sensōji temple.

Despite its formidable sounding name, the gate was burnt down several times throughout history. Quite an irony, we would say, given that the enshrined Gods of Wind and Thunder are supposed to guard the temple from storm, flood, and fire.

Kaminarimon in 1967

Image credit: Kotsu metro

The temporary wooden gateway remained for nearly 100 years until the current one was built thanks to a generous donation from the founder of Panasonic, Kōnosuke Matsushita.

Panasonic’s name, formerly known as Matsushita Electric (松下電器), etched on the lantern

Image credit: @tokyovisite

Matsushita suffered from an illness and went to Sensōji temple to pray for a cure. Fortunately, his prayers were answered and he regained his health. As a token of gratitude, he donated the gate and the large lantern, which became the Kaminarimon we know today.

Till today, the giant red lantern hung at the gate is inscribed with the kanji characters “松下電器” (Mashita denki), Panasonic’s former name.

Address: 2 Chome-3-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo 111-0032, Japan

6. Shibuya Crossing – Tokyo

Shibuya crossing in 1952 (left) and 2020 (right)

Shibuya crossing in 1952 (left) and 2020 (right)

Image adapted from: @pppqqq and @alafista

An epitome of Tokyo’s urban landscape, the Shibuya Crossing is perhaps the busiest intersection in the world – there is no end to traffic even at night or in the wee hours of the morning.

Image credit: @linglivestolaugh

Image credit: @linglivestolaugh

Shibuya Crossing first became widely known abroad when it was featured in blockbusters like Lost in Translation and Resident Evil. The orderly fashion and skillful maneuvering of Japanese pedestrians from all four sides, without bumping into each other, is particularly fascinating for foreigners.

Heavy traffic at Shibuya crossing in 1953

Image credit: Kaikai hannō tsūshin

In recent years, the intersection has become a symbolic centre for youths to gather at and revel till dawn during Halloween or New Year’s Eve. The festive ambience makes for a unique experience, though the streets are so packed that one can barely move an inch.

Address: 2 Chome-2-1 Dogenzaka, Shibuya City, Tokyo 150-0043, Japan

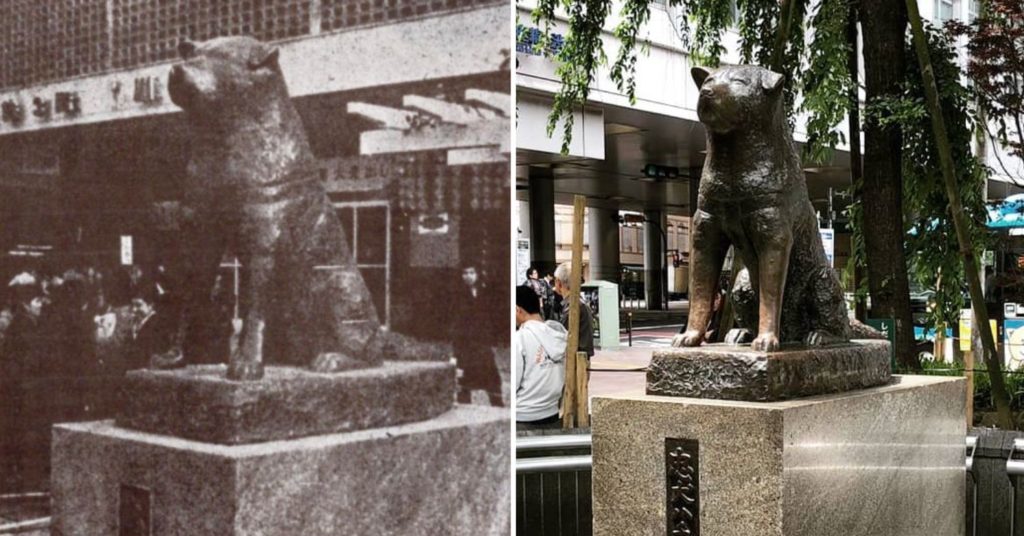

7. Hachiko Statue – Tokyo

Statue of Hachiko in 1958 (left) and 2019 (right)

Statue of Hachiko in 1958 (left) and 2019 (right)

Image adapted from: Japan Archives and @chancellorwoofs

An exemplary role model to all, the Hachiko Statue commemorates the Japanese Akita dog who was fiercely loyal to his owner, Hidesaburo Ueno.

Every morning, Hachiko would accompany his owner, a professor at the University of Tokyo, to Shibuya Station for his commute to work. By the end of the day, Hachiko would return to the same station to greet the professor, and they would walk home together.

British soldiers with Hachiko in 1955

Image credit: Japan Archives

The daily routine continued until Professor Ueno suffered from brain hemorrhage while he was giving a lecture, and never returned. Hachiko continued to show up at the station everyday, and waited for his owner for nearly 10 years until his death in 1935.

His faithfulness to his master is widely considered by the Japanese to be an example of familial loyalty for all to follow.

Hachiko waiting for his owner

Image credit: Livedoor

Nowadays, the bronze statue is a convenient meeting point when one is in Shibuya. Locals would often agree on meeting “in front of Hachiko” (ハチ公前), as there are signs within the station clearly directing commuters to the Hachiko exit.

Address: 1 Chome-2 Dogenzaka, Shibuya City, Tokyo 150-0043, Japan

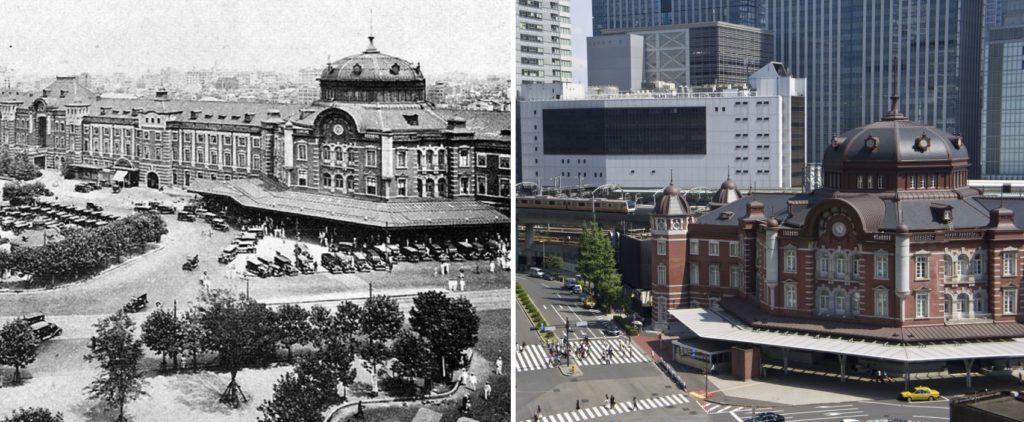

8. Tokyo Station – Tokyo

Tokyo Station in 1914 (left) and 2015 (right)

Tokyo Station in 1914 (left) and 2015 (right)

Image adapted from: Wikimedia and Curazy

The conceptualisation of Tokyo Station started from an idea to establish a central stop by connecting various train lines.

Tokyo Station in 1945

Tokyo Station in 1945

Image credit: Japan Archives

A Japanese–style building was initially proposed by German engineers Hermann Rumshottel and Franz Baltzer. However, as Japan was working towards Westernisation back then, due to the ongoing Meiji Restoration, the design garnered a lukewarm response.

For that reason, the station was redesigned by Kingo Tatsuno, who was an established pioneer of modern Japanese architecture.

Image credit: @nathadej

The station building was completed in 1914 and miraculously survived the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. Unfortunately, it was not spared from the damages inflicted by air raids during World War II.

Restoration works then resumed in 2007 after the station building was designated as a National Important Cultural Property in 2003.

Address: 1 Chome Marunouchi, Chiyoda City, Tokyo 100-0005, Japan

9. Ginza – Tokyo

Wako Clock Tower in 1955 (left) and 2018 (right)

Wako Clock Tower in 1955 (left) and 2018 (right)

Image adapted from: Metro Archive and @ultraodel

Perhaps the most recognisable landmark of the shopping district, the Wako Clock Tower stands tall at the corner of Ginza yonchome intersection.

Despite the area’s elegant reputation today, it was not always the case. Large fires frequently occurred in the past as wooden houses lined the streets of Edo – the former name of Tokyo. The city upgraded each time a big fire occurred. After a major fire in 1872, the idea of rebuilding the town with bricks was formed.

View of Ginza Intersection in the 1930s

Image credit: Wikipedia

Japan was in the midst of Westernising and they saw this as another opportunity to adopt Western architecture. With multiple fire-resistant buildings constructed using bricks, Ginza became known as the “Bricktown”.

Ginza Chuo-dori on Sundays and public holidays, when it gets closed off to traffic

Image credit: @john_cameron

Not only were Western architecture adopted, but stores also changed the long-standing business model in Japan. While established stores in older districts only brought out items from the back of the store when requested, Ginza stores had show windows that displayed the products.

Moga (モガ) walking along the streets of Ginza in the early Shōwa Period

Image credit: Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Realty Co

Window shopping in Ginza was a fad that took the nation by storm. It was the trendiest place to be for moga (モガ) and mobo (モボ), short for “modern girl” and “modern boy” – independent fashionable youths. These days, it is better known as an upmarket shopping district where old money shops.

Address: 5 Ginza, Chuo City, Tokyo 104-0061, Japan

10. Ōdōri Park – Sapporo

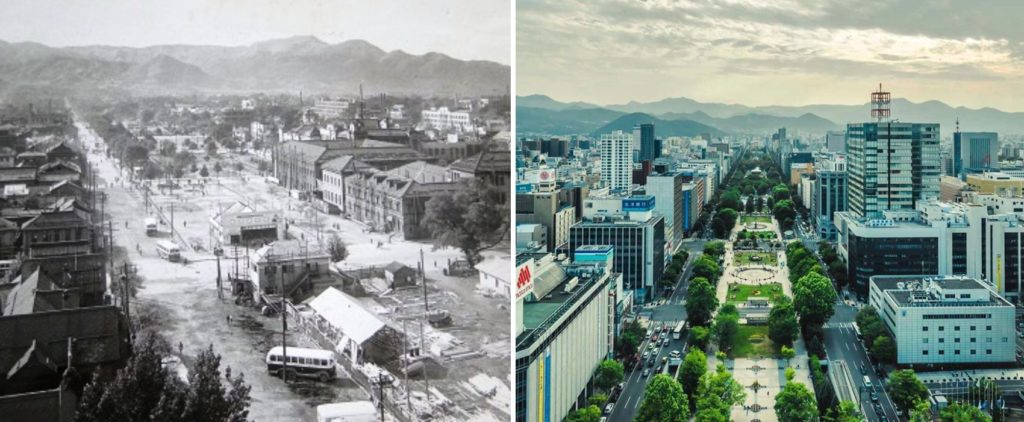

Ōdōri park in 1951 (left) and 2019 (right)

Ōdōri park in 1951 (left) and 2019 (right)

Image adapted from: Sapporo Jouhoukan and @ksy.yuan

Situated between the government office district in the north, and residential and commercial buildings in the south, Ōdōri Park was built in 1871 to function as a firebreak.

Today, it is the venue for most of the city’s seasonal events, such as Sapporo Snow Festival in winter and Sapporo Ōdōri Beer Garden in summer.

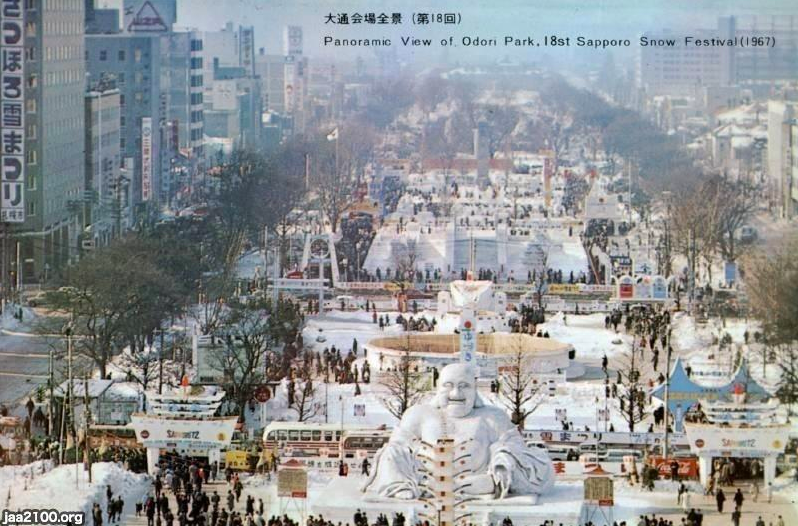

Sapporo Snow Festival in 1967

Image credit: Japan Archives

Spanning 1.5 kilometres and covering 13 blocks, Ōdōri (大通り) means “large street” in Japanese.

Address: 7 Chome Odorinishi, Chuo Ward, Sapporo, Hokkaido 060-0042, Japan

11. Dōtonbori – Osaka

Dōtonbori in the 1880s (left) and 2020 (right)

Dōtonbori in the 1880s (left) and 2020 (right)

Image adapted from: Old Photos of Japan and @onedayinport

Dōtonbori and Ebisu Bridge are famous downtown areas in Osaka that have been prosperous since the 1880s.

Dōtonbori in around 1900

Image credit: @japan_time_travel

The surrounding area used to be known as Osaka’s entertainment district as there were a myriad of kabuki and bunraku theatres.

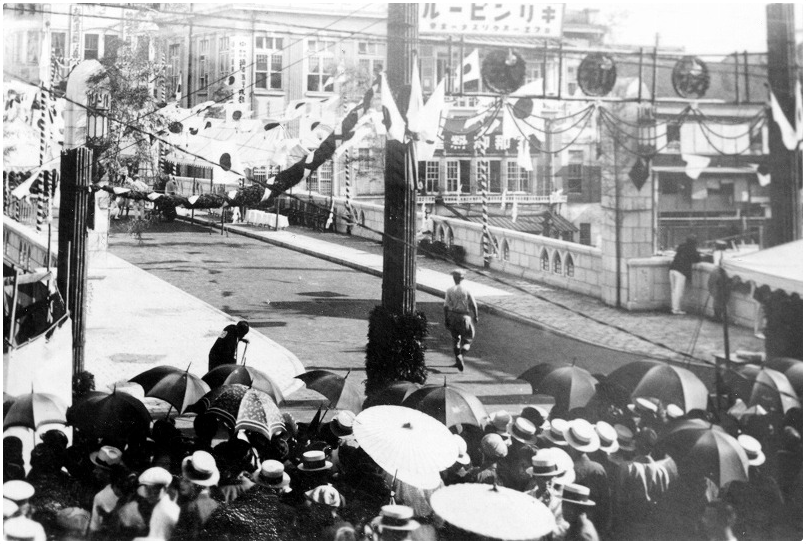

Opening of the new Ebisu bridge

Image credit: Dōtonbori Official Site

Although the surroundings have been replaced with gaudy neon lights and eye-catching signage, the canal remains unfilled amidst Osaka’s rapid development. Till today, Dōtonbori is a must-visit leisure and entertainment district for locals and tourists.

Address: 1 Chome-9 Dotonbori, Chuo Ward, Osaka, 542-0071, Japan

12. Arashiyama Bamboo Forest – Kyoto

Bamboo forest in 1915 (left) and 2020 (right)

Bamboo forest in 1915 (left) and 2020 (right)

Image adapted from: @japan_time_travel and Mike Kniec

One of the most well-known sites of the ancient city of Kyoto, the lush woods of bamboo and cool winds of Arashiyama transport visitors to a serene world.

Around the 8th century, there was a congregation of noble villas in Arashiyama as the Japanese aristocrats frequently visited the area for their vacations.

Image credit: @thevisualiza

Image credit: @thevisualiza

The Arashiyama Bamboo Forest hasn’t changed much, except that it is now loved by people in Japan and abroad.

In 1996, in an attempt to combat noise pollution and encourage environmental preservation, the Japanese government designated the rustling sound of bamboo as part of 100 Soundscapes of Japan.

Address: Ukyo Ward, Kyoto, 616-0007, Japan

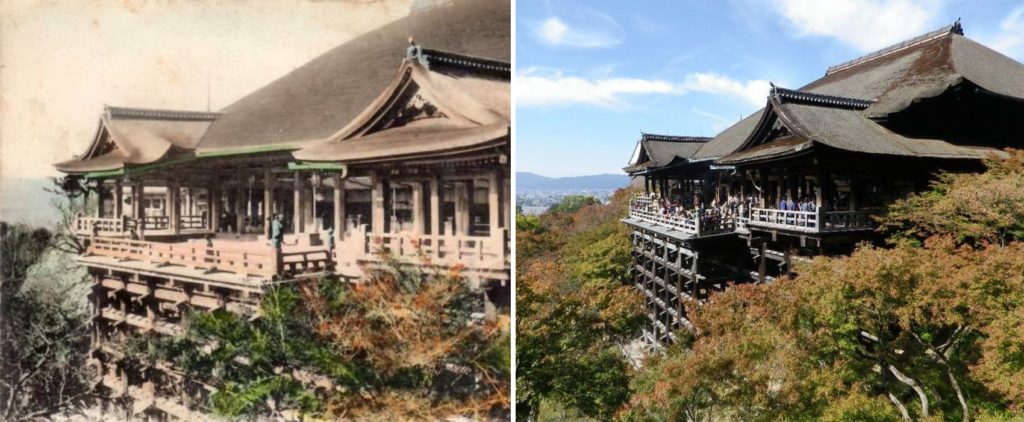

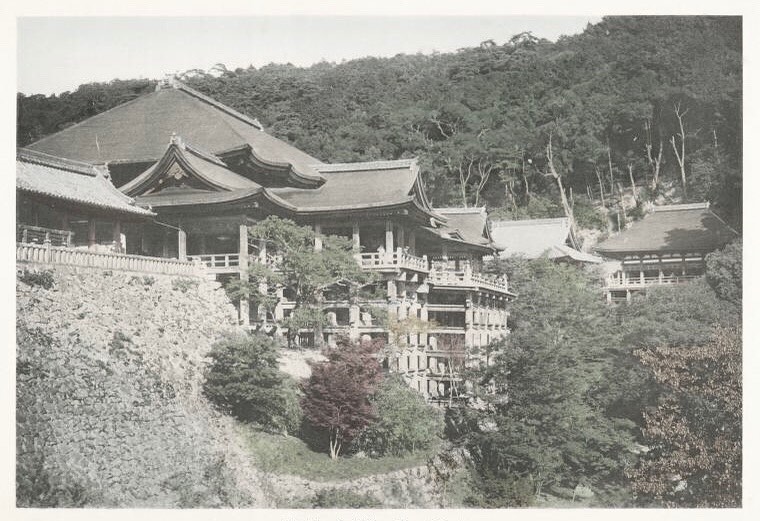

13. Kiyomizu-dera – Kyoto

Kiyomizu-dera in 1910 (left) and 2015 (right)

Kiyomizu-dera in 1910 (left) and 2015 (right)

Image adapted from: Japan Archives and RCJ00

With over 1200 years of history, Kiyomizu-dera is one of the few historical temples that existed before the Heian period – when Kyoto was established as the capital of Japan.

Kiyomizu-dera in early 1900s

Image credit: @japan_time_travel

Legend has it that a Buddhist monk was told in his dream to head to the Kizu River. He followed the golden stream of water and arrived at the foot of Mount Otowa, where Otowa Waterfall is located.

The name “Kiyomizu dera” (清水寺), which translates to “pure water temple”, originated from the clear water that flows through Otowa Waterfall.

Image credit: @ironstagram

Image credit: @ironstagram

The temple’s wooden terrace has stood well against the test of time, thanks to its architectural ingenuity. Without using a single nail, Japanese carpenters carved out holes and grooves, and then combined the pillars to form the wooden platform.

Address: 294 Kiyomizu, Higashiyama Ward, Kyoto, 605-0862, Japan

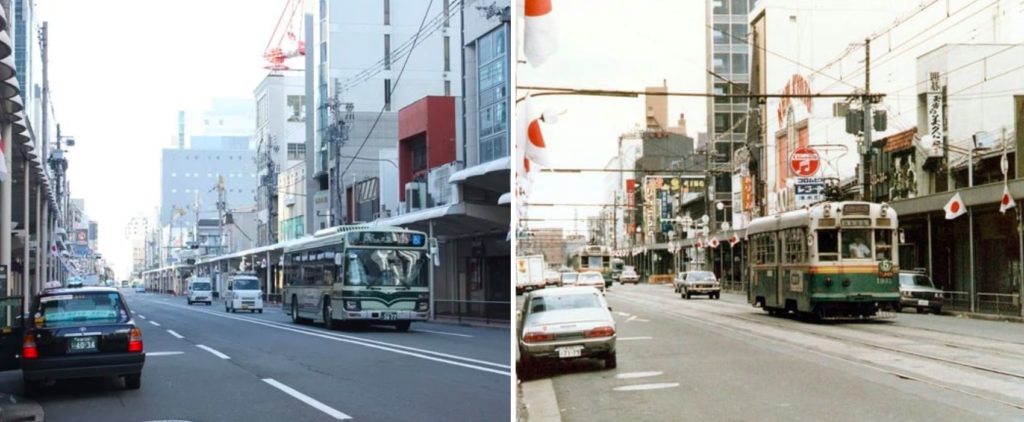

14. Kawaramachi Street – Kyoto

Kawaramachi street in the 1970s (left) and 2019 (right)

Kawaramachi street in the 1970s (left) and 2019 (right)

Image adapted from: Kyoto no osanpo and Kyoto no osanpo

Kawaramachi Street is the go-to shopping district in Kyoto. Here, tradition and modernity coexist – you can find the trendiest fashion shops alongside old establishments selling Kyoto crafts or traditional food.

The exact opening date is unknown, but it is believed to be during the rule of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who is widely regarded to be one of the Great Unifiers of Japan. By the end of the Edo period, samurai residences and temples filled the area.

City trams in 1970s Kyoto

Image credit: biglobe.ne

Trams used to run the streets of Kawaramachi-dori, but they were shut down in 1978 due to the increase in traffic.

Kamo River in summer

Kamo River in summer

Image credit: @andreslyu

For exhausted shoppers, the nearby Kamo River is perfect for a relaxing stroll after a long day of shopping.

Address: Kawaramachi-dori St, Shimomaruyachō, Nakagyo Ward, Kyoto, Japan

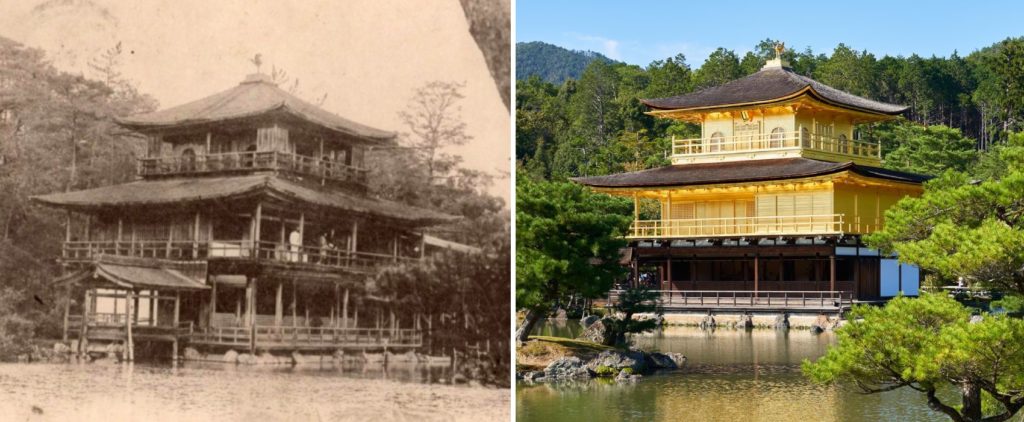

15. Kinkaku-ji (Golden Pavilion) – Kyoto

Kinkaku-ji in 1908 (left) and present (right)

Kinkaku-ji in 1908 (left) and present (right)

Image adapted from: Japan Archives and @magict1911

An opulent temple with its main pavilion completely covered with gold leaf, Kinkaku-ji is a quintessential Kyoto landmark. The temple’s official name is Rokuon-ji, but the golden reliquary hall is so famous that the entire compound is referred to as Kinkaku-ji.

Kinkaku-ji in around 1910

Image credit: @japan_time_travel

Originally a villa, Kinkaku-ji belonged to a Japanese aristocrat from the 12th to 14th century. However, it was taken over by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third shōgun of the Muromachi Shogunate, to build his own villa. Upon his death, the building was converted into a temple.

Address: 1 Kinkakujicho, Kita Ward, Kyoto, 603-8361, Japan

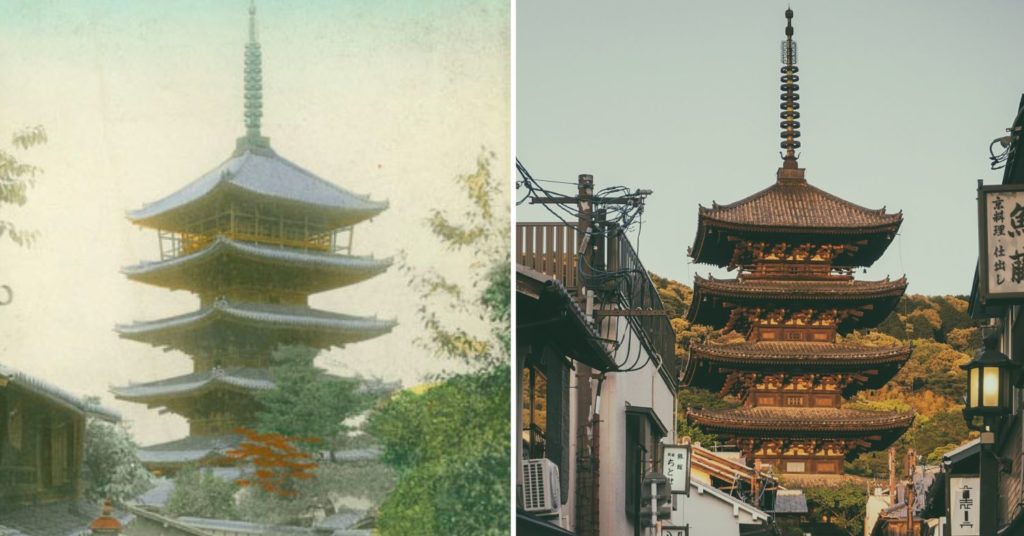

16. Yasaka Pagoda – Kyoto

Yasaka Pagoda in the 1910s (left) and present (right)

Yasaka Pagoda in the 1910s (left) and present (right)

Image adapted from: Old Photos of Japan and @daniel840528

One of the most prominent and photographed icons of Kyoto, Yasaka Pagoda remains extant in the ever-changing Higashiyama area. With just ¥400 (~USD3.81), visitors can climb to the second floor to get an amazing view of the historic district.

Image credit: @boontohhgraphy

Image credit: @boontohhgraphy

As it is a popular spot among photographers to capture the sunset, the main street might get over-crowded in the evening. If that happens, simply escape to the less–frequented side lanes and explore the nooks and crannies the old district has to offer.

Address: 388 Yasaka Kami-machi, Kiyomizu Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto City

17. Himeji Castle – Himeji

Himeji castle in 1910 (left) and present (right)

Himeji castle in 1910 (left) and present (right)

Image adapted from: Old Photos in Japan and @nierozpakowani

Due to its pristine white facade, Himeji Castle is widely regarded as one of the most well-preserved and impressive castles in Japan.

Himeji Castle from a distance in 1984 (left) and 2020 (right)

Himeji Castle from a distance in 1984 (left) and 2020 (right)

Image adapted from: Japan Archives and @thomas185jp

Unlike many other Japanese castles that have been destroyed due to wars, earthquakes, and fires, Himeji Castle has survived to this day in its original form.

Repair works in 1962

Image credit: Hyogo Odekake Plus+

From 1956 to 1964, the castle underwent large-scale repair work – the main tower was dismantled and the castle foundation was reinforced with concrete. The large-scale preservation works proved to be useful, as the castle remained largely intact during the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake.

Address: 68 Honmachi, Himeji, Hyogo 670-0012, Japan

18. Chinatown – Yokohama

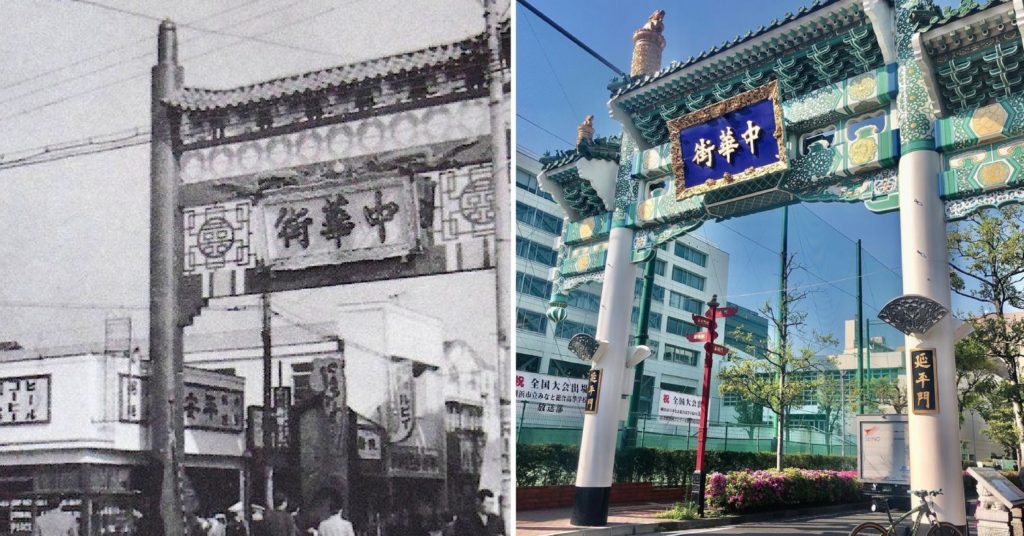

Yokohama Chinatown in 1975 (left) and 2016 (right)

Yokohama Chinatown in 1975 (left) and 2016 (right)

Image adapted from: Bank of Yokohama and Bank of Yokohama

Yokohama Chinatown is Japan’s largest Chinatown, with history dating back to 1859. As one of the first Japanese ports to open to foreign trade, Yokohama Port quickly became the residence of many Chinese immigrants.

Chinese settlers from Guangdong, Shanghai, and other parts of China set up their businesses in central Yokohama.

Chinatown entrance in 1955 (left) and 2020 (right)

Chinatown entrance in 1955 (left) and 2020 (right)

Image credit: Yuki and @toru.na72

The area became a bustling trading port as Chinese traders would import and export food products from neighbouring East Asian countries. Today, the area has more businesses than residents, and visitors can indulge in authentic Chinese food like fried dumpling soup and Peking duck.

Address: Yamashitacho, Naka Ward, Yokohama, Kanagawa 231-0023, Japan

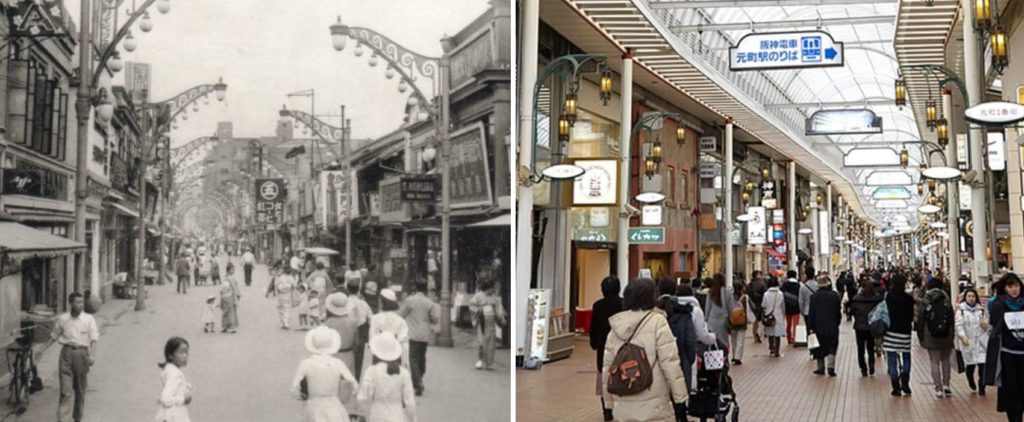

19. Motomachi Street – Kobe

Motomachi street in pre-war Kobe (left) and present (right)

Motomachi street in pre-war Kobe (left) and present (right)

Image adapted from: @yonezawakouji and Kobe Motomachi 1st Street

With more than 140 years of history, Motomachi Street is Kobe’s best-known shopping street. First developed after the opening of the Port of Kobe in 1868, the area flourished under the booming economy due to World War 1 and became the leading commercial district in the city.

1927 Motomachi Street lined with suzuran lamps

Image credit: Japan Archives

In order make the streets more attractive, decorative lily-shaped street lamps named suzuran-tō (鈴蘭灯) were installed along the streets in 1926, creating a lively atmosphere in the nighttime.

Address: Motomachidōri, Chūō-ku, Kobe, Hyogo 650-0022, Japan

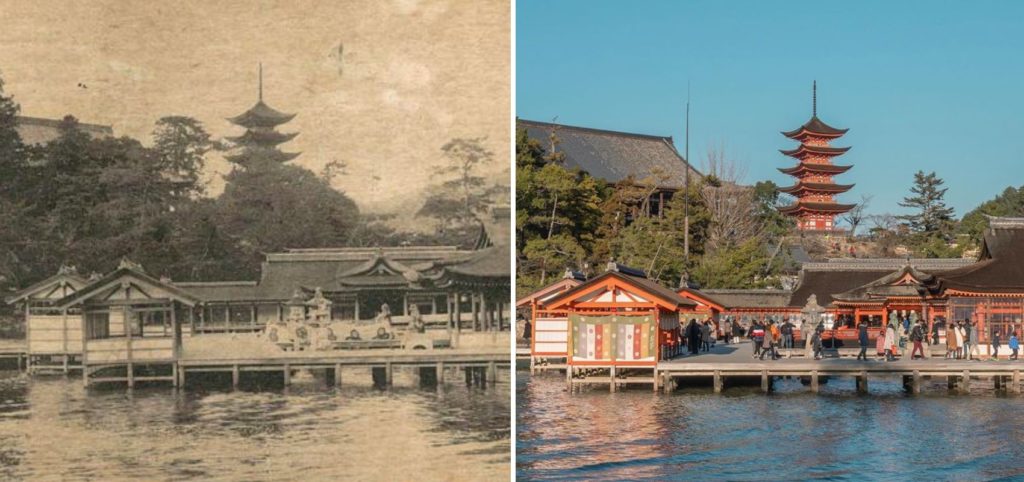

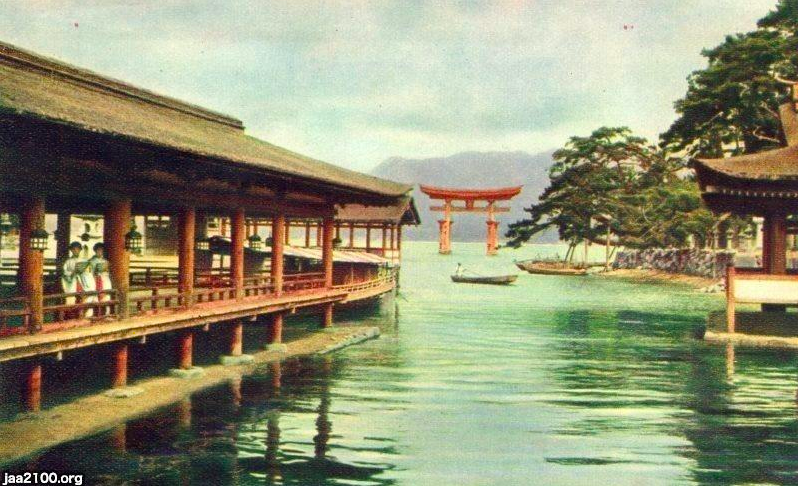

20. Itsukushima Shrine – Hiroshima

Itsukushima shrine in 1925 (left) and 2020 (right)

Itsukushima shrine in 1925 (left) and 2020 (right)

Image adapted from: Japan Archives and @xxsea23xx

Best known for its “floating” torii gate, Itsukushima Shrine is located in Miyajima, a small island in Hiroshima Bay.

In case you’re wondering why the torii gate is built over water, it is believed that the kami (gods) inhabit the island. Thus, chopping down trees to make way for the construction of a torii gate was considered blasphemous.

Itsukushima shrine in 1936

Image credit: Japan Archives

Not much has changed when comparing the past and present. This may come as a surprise, as one would expect the wooden structure to decay and rot under water. To prevent that from happening, kusunoki (camphor trees) was used during construction as it does not rot easily.

Image credit: @haltakov

But it doesn’t mean that the gate will remain in tip-top condition forever – repair works have been going on since June 2019, and is expected to last till summer this year.

Address: 1-1 Miyajimacho, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima 739-0588, Japan

Iconic landmarks in Japan then and now

Japan has seen major upheavals throughout history. Though some places have changed beyond recognition, others have survived well amidst rapid development. The country seems to have found a formula for history and the present to coexist. As these photos show, it is not uncommon to see a well-preserved shrine or temple situated among ultra-modern skyscrapers.

Check out these articles for more Japan related content:

- Onigiri rings for foodies

- Weird Japanese mascots

- Influential Japanese photographers

- Interesting Japanese inventions

- Unusual facts about Japan

Cover image adapted from: Japan Archives and @xxsea23xx